This embellished list by Alan Light is well worth going through. They’re the greatest hits, for the most part, but many of the notes were new to me.

As was this song, which Light notes he wrote while in jail, without a map.

This embellished list by Alan Light is well worth going through. They’re the greatest hits, for the most part, but many of the notes were new to me.

As was this song, which Light notes he wrote while in jail, without a map.

Last April The Biletones went into the studio to drop down five tracks for an EP, and while we were at it, a friend of the band, Andre Welsh, who does camera work in Hollywood, agreed to video the band in action. It was kind of fun and intense, but also ugh city.

As in for the Route 66 video, we played the song 11 times so the film crew could focus on different aspects and players during the song.

The four remaining tunes we played were It Takes a Lot to Laugh (check out Steve Gibson’s killer solos), It’s All Over Now (I sing lead), Don’t Cry no Tears, and lead singer Tom Nelson’s Rich Girlfriend. Do click to the third cut and check out Girlfriend. It is one of our strongest tunes (it is third on the playlist in the upper right corner of the Route 66 vid).

Everybody who knows the Internet K-Hole says they love the Internet K-Hole. I’ve previously said it here and here.

Everybody who knows the Internet K-Hole says they love the Internet K-Hole. I’ve previously said it here and here.

Someone at Cuepoint has taken 32 pictures from the hole and matched them to lyrics from songs. Some are great lyrics, some match the photo, some seem a little random, but it’s all good.

Enjoy.

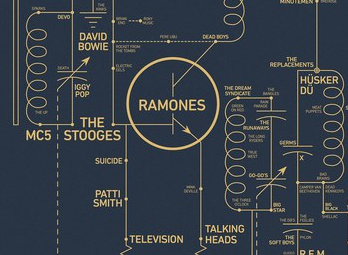

A design studio named Dorothy has released a survey of alt-rock music based on the schematic design of a transistor radio that came out in 1954, the year Bill Haley released Rock Around the Clock.

A design studio named Dorothy has released a survey of alt-rock music based on the schematic design of a transistor radio that came out in 1954, the year Bill Haley released Rock Around the Clock.

That’s a detail from a much larger image over to the left.

I’m not sure about the information included in the diagram. I mean why do the Ramones lead to Mink Deville lead to Talking Heads.

Why is Elvis Costello in smaller type than the Specials?

Why aren’t the White Stripes next to the Black Keys?

There are many of these questions, which seem to be answered rather randomly. That said, there is a broader logic as to time and place and style, and it’s good fun browsing using the magnification tool. h/t Herrick Goldman.

The rock writer Jack Hamilton is publishing a book called Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. It’s an academic work, but a part of it is excerpted at Slate today and it’s well worth the slow start and long read.

The rock writer Jack Hamilton is publishing a book called Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. It’s an academic work, but a part of it is excerpted at Slate today and it’s well worth the slow start and long read.

Hamilton’s thesis is that the Stones were so adept at embracing and mirroring the black music they loved, that they eventually came to represent a new white authenticity that was embraced by white blues and metal bands that knew little or nothing about the Stones’ roots.

You can read the excerpt here.

I’m not sure what this means in the book’s larger picture, it is an excerpt of course, but without looking at the argument’s validity as regards the whole history of rock ‘n’ roll, this little slice of story feels kind of genuine. Like, yeah, that may be true, though he have maybe set up something of a straw man argument, too. Still feels like useful analysis.

But Hamilton draws in a lot of historical sources to tell this story, and it’s fascinating to read quotes in the black newspapers of 1964 praising the Stones, while the mainstream white press rips them down. And his description of the musical opening of Gimme Shelter is exact and thrilling, like the music itself.

It’s curious that the Margo Jefferson quote from earlier in the piece comes from 1973, which was also a germination point for Death, who we posted about here last week. It’s possible that this book will shed some light on the way rock ‘n’ roll evolved musically and as a business in a racial context.

Then, if you have time, Chuck Klosterman tries to figure out who the one figure from rock ‘n’ roll will be remembered 100 years from now, the way we think of marching band music as John Phillips Sousa and ragtime as Scott Joplin.

There was a story in yesterday’s NY Times about Harley Flanagan, who has always been a presence in the NY rock scene. Most notably as the drummer bass player in the Cro-Mags, one of the most notable bands of the city’s hard core scene in the 80s. All age shows at CBGB in the afternoon were a fixture, and perhaps explain why I never really paid much attention. Too old! But this clip is terrific, reminds me of Penelope Spheeris’s fantastic movie, Suburbia, and it even better than that. You probably won’t want to listen to it all the time, but I hope you enjoy it first time through.

Prince is pretty famous for not licensing any of his music to any streaming service but Jay Z’s Tidal.

But he should also be famous for initiating many online services with various plans to serve music and publicity and other ideas over the years. After all, he was a major artist who went indy after his falling out with Warner Brothers.

He left the label, but they owned his music, so he presented himself as a slave and wouldn’t use the name Prince, since that was his slave name.

Prince’s various online ideas have now been collected at the PrinceOnlineMuseum.com. I’ve only browsed so far, so I have no tips, but this is stuff Prince did online.

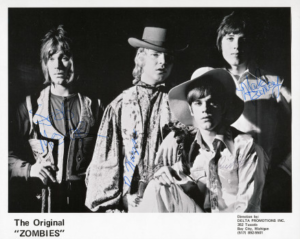

This is a terrific story about fake bands in the late 60s, touring the states as bands like the Zombies (pictured, wearing cowboy hats) and the Animals, and one particular band that went on to make it’s own music after the jig was up.

This is a terrific story about fake bands in the late 60s, touring the states as bands like the Zombies (pictured, wearing cowboy hats) and the Animals, and one particular band that went on to make it’s own music after the jig was up.

Alex Pareene has a story about an album Prince recorded for a covers record in 1993, and a clip of his power trio playing Honky Tonk Women, which is pretty swell. Read and hear it here.

There is a somewhat long piece by Brent L. Smith on Medium, linked here. It starts from a quote from Dylan in that interview he did last year in the AARP magazine, in which he says that payola was a force that caused rock ‘n’ roll in the 50s to split into rock (white) and soul (black) music in the 60s.

Smith covers a lot of ground in support of this idea, including the rise of DJs, doo wop’s role in the cleaving, the historical role of the tavern in the American multiracial democracy (and the elite’s disdain for the tavern and the multiracial democracy), Norman Mailer’s essay about the rise of the white Negro, a nod to Chuck Berry as poet and guitar master, and, of course, Jimi Hendrix. Which leads Smith to some talk about the fourth wave of garage rock he says is going on now, linking to the LA magazine, Janky Smooth, at which he works.

One of the highlights are competing quotes from Frank Sinatra and Dr. Martin Luther King decrying rock ‘n’ roll, which make that music of the 50s sound really dangerous.

Smith’s writing is loose limbed, I couldn’t always figure out where the quotes came from, and some word choices are, um, interesting. Smith is a graduate of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, which perhaps literally explains some of that, but the ambition and breadth of his ideas and their connections with each other are nothing if not provocative. You will miss having a genuine soundtrack to listen along to while reading. Here it is.