He was 56 years old. The band’s guitarist was diagnosed with cancer in 2007. He wrote “Thousands Were Sailing,” among others.

Category Archives: tribute

The 11 Best of Lucinda Williams: The Dallas Observer and Rock Remnants

I saw on Facebook today that the Dallas Observer had a feature listing Lucinda Williams’ 11 best songs. Williams is one of my favorite songwriters and performers and, without looking at the Observer’s list, I thought it might be a nice challenge to come up with my own 11 favorites. Here goes:

“Passionate Kisses,” Lucinda Williams

Pretty much a perfect pop song, though the arrangement here (as on this third album as a whole) is a little too clean and pretty. Or, maybe, not shiny and slick enough for pop radio. Mary Chapin Carpenter’s cover was a big hit.

“Pineola,” Sweet Old World

Harrowing story-song that crawls forward into the deepest of griefs, then explodes into a howl of defiance and resignation.

Live version of Pineola, plus Drunken Angel (which is listed below).

“I Lost It,” Car Wheels On a Gravel Road

An oldie from Happy Woman Blues that she rerecorded with the hard rocking band that defined her sound in the middle years. The 1980 version is lovely, sounds as classic as a Hank Williams track, while this is slower, more bluesy, more pounding, like a Hank Williams Jr. track (without the cheese).

“Drunken Angel,” Car Wheels on a Gravel Road

Sneering angry rant, makes the feet tap and the skin crawl.

“Greenville,” Car Wheels On a Gravel Road

Achingly sad breakup song, with Emmylou Harris singing harmonies (on the record, not the clip).

“Metal Firecracker,” Car Wheels On a Gravel Road

Has the poppy spright of Passionate Kisses, but delivers a breakup song full of hurt and a wishful rewriting of history in plain lovely language that kicks off on an irresistible hook.

“Lonely Girls,” Essence

Simple poetic language and a subtle folky reggae setting, doesn’t really go anywhere and doesn’t have to. I could listen to this all day.

“Essence,” Essence

A churning insistent atmospheric punch of love, it is at this point in her career her most naked expression of masochistic surrender, except that if this is surrender I’d hate to see the war.

“Changed the Locks,” Live at the Fillmore

The studio version on the Lucinda Williams album has the bones of a great song, but this live version is loud and scratchy and a full expression of the song’s anger and defiance.

“Fancy Funeral,” West

Plain and plaintive observation following her mother’s death. More intimate for its impersonal but poignant details.

“Honey Bee,” Little Honey

A flat out rocker that sounds more like her live band rampaging through that Texas rock sound that ZZ Top (maybe) invented.

Conclusion: Many shared tunes with the Dallas Observer, it turns out, and many differences. A note about Side of the Road, their No. 1 (they ordered their list, mine is chronological) tune. It’s a fantastic story song, as the writer says, sad and yet not depressing, an evocation of being a person in something larger than yourself but not sure where that ends and you begin. I left it off my list because I’ve always found the verse about looking up at the farmhouse a little clumsy, and that’s a fair judgement perhaps, but playing it again just now I’m reminded about how great a song it is despite that. It should be on my list of 12.

My radio and me in 1972-73

Just traveled to California and drove up and down Laurel Canyon and thought not only about Joni Mitchell, who has been such a source of controversy here, mostly backstage, but my love of music very generally and where it began.

In 1972, my mother moved us (parents were divorced) to the Mojave Desert — Yucca Valley, CA. Geologically and geographically different from Laurel Canyon, yet sharing that same artsy vibe (only the poor artists live in the desert).

The people we hung with, the new friends and relatives, aunts and uncles I hardly knew, were mostly listening to that Canyon music — Mitchell, Carole King, Carly Simon, Todd Rundgren, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, Seals and Crofts and, of course, some non-California acts like the Rolling Stones.  (I especially remember the hours I spent staring at Goats Head Soup’s cover and how horrified I was of the image of that soup where, now, what’s truly horrifying about that album is how it marked the beginning of the end of the greatest Rock and Roll Band in the world.)

(I especially remember the hours I spent staring at Goats Head Soup’s cover and how horrified I was of the image of that soup where, now, what’s truly horrifying about that album is how it marked the beginning of the end of the greatest Rock and Roll Band in the world.)

At gatherings, the adults provided the soundtrack. But back home, in my room, lying on my waterbed, the radio was the only free form of entertainment I had. The scoops of ice cream cost $.05 cents at Thrifty’s and I think the occasional drive-in was $5 per car. I was before and am again now a TV junkie. But I never even saw a TV at any adult’s house. Not only was it looked down upon, but there was no reception in the high desert. Yet I still stubbornly spent many hours the first few weeks, maybe even few months, trying to get some signal from the black and white set I badgered my mother into bringing west. Alas, there were only faint ghosts of images, and only at night — nothing remotely watchable or even listenable. (Yes, I would have given anything to even LISTEN to TV.) So all that was left for me was my transistor radio — this model, I swear.

Only the Hits station came in. I can’t say if that period was particularly good for music — that would be like asking the starving man to rate the hamburger you just gave him. But 1972’s top 100.it sure seemed good to me.

I loved “American Pie,” it was the first time I really noticed dramatic changes in sound within one song. And it was the first song where I really paid attention to the lyrics. “Brand New Key” by Melanie was inescapable. I didn’t like it then or now. But another kitschy song, “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” was pure childhood delight for me. I loved “Alone Again (Naturally),” oblivious to how sad it was. My love of soul music was forged here: “I Gotcha” by Joe Tex was most popular but I preferred Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together,” “Lean on Me” by Bill Withers, “I’ll Take You There,” “Backstabbers,” “Oh Girl”…. I heard them all so many times that I may as well have owned the records (which nine year olds don’t buy even if they could afford to, which I couldn’t).

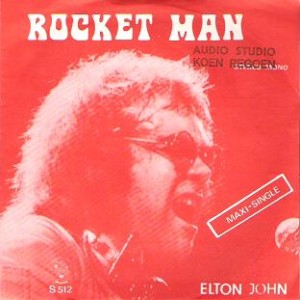

“Rocket Man” by Elton John sounded different from everything else, yet was so catchy and was the first time I heard one of those great Elton choruses that I grew to love so much.  While I really liked more iconic, Rock Remnants-certified rockers like “Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress” by the Hollies, “Go All the Way” by the Raspberries and “Bang a Gong” by T-Rex, I had ample room in my juvenile musical palate for Cat Stevens’s “Morning Has Broken,” too. That was the first time I really noticed how beautiful a piano could sound. I could hardly afford to hate much when hating required me to turn off the radio and thus my only connection to the outside world. I looked for things I liked in everything I heard and if I really hated something, like Melanie, I had to tolerate it anyway and give it every chance to change my mind (as some songs did — like “Hocus Pocus” by Focus — learned to love the guitar riffs, still hated the yodeling.)

While I really liked more iconic, Rock Remnants-certified rockers like “Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress” by the Hollies, “Go All the Way” by the Raspberries and “Bang a Gong” by T-Rex, I had ample room in my juvenile musical palate for Cat Stevens’s “Morning Has Broken,” too. That was the first time I really noticed how beautiful a piano could sound. I could hardly afford to hate much when hating required me to turn off the radio and thus my only connection to the outside world. I looked for things I liked in everything I heard and if I really hated something, like Melanie, I had to tolerate it anyway and give it every chance to change my mind (as some songs did — like “Hocus Pocus” by Focus — learned to love the guitar riffs, still hated the yodeling.)

1973’s top 100 gave me “Me and Mrs. Jones” by Billy Paul, which seemed so grown up and off limits, but man, did I love it on those lonely desert nights while trying not too hard to go to sleep. But I also loved polar opposite songs like “Frankenstein” by Edgar Winter (Hocus Pocus without the yodeling!) and “Little Willy” by Sweet, which may as well have been The Archies to my ear. It was pure kid music, barely less silly than “The Monster Mash,” another 1973 hit. And about monsters! “Will It Go Round in Circles” by Billy Preston was a pleasure for me every time, as was “Superstition,” “Stuck in the Middle with You,” “Live and Let Die,” “Daniel,” “Superfly,” “Love Train,” “That Lady” and the also-so-grown-up “Wildflower” by Skylark. “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” seemed like it was written just for nine-year-old boys and how could it be that this song inspired Freddie Mercury of all people? Music is such a wonderful chemistry experiment, a fact that comes into sharp relief when you can do nothing else but immerse yourself in it for two, long formative years.

From the Archives: 30 Greatest R&R Guitarists (circa 1980)

How much have about 30 years altered this list that was put together by Dave Marsh in the Book of Rock Lists? We have a few guitarists on the site, so I’m interested to see what they think.

Mickey Baker

1. Jimi Hendrix

2. Chuck Berry

3. Mickey “Guitar” Baker (Mickey and Sylvia, sessions)

Steve Cropper

4. James Burton (Elvis)

5. Pete Townshend

6. Keith Richards

7. Scotty Moore (Elvis)

8. Steve Cropper (Booker T. and the MGs)

9. Link Wray

10. Eric Clapton

Other notables when the list was published in 1980/81: Eddie Van Halen (13), Duane Allman (17), Jimmy Page (22), Mick Jones (24), Steve Jones (25), Bruce Springsteen (29).

As much as I love Springsteen and his guitar playing, I wouldn’t have him on this list. I’d put Prince in the top 30, though I don’t know where. I’d have Mick Taylor (29) higher. I’d have Marc Bolan and Mick Ronson on the list. Jimmy Page would be in my top 10 because he wrote so many great riffs but I know that a lot of guitar players think he’s sloppy. I can’t hear it though. I think Tom Morello belongs on the list after seeing him with Springsteen.

I remember talking to Moyer years ago about guitarists and I questioned the extent that leads should influence the rankings and he said that there isn’t a great guitarists who didn’t play great leads. I countered with Keith Richards and Steve had to admit that I had him there. Of course, Richards played, and wrote, many of the greatest riffs in rock history.

Jefferson Airplane: THE Best San Francisco Band

I guess the news of ex-Jefferson Airplane/Hot Tuna drummer and percussionist Joey Covington’s passing earlier this week sort of pushed the thoughts I have always had about the Airplane into this virtual-osity.

I think of all the San Francisco bands–especially those who bore the “psychedelic” moniker–the Airplane were the truest to the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll.

True, The Dead were a great band,but they were a jam band. Big Brother was a great band, but they were a blues band. Quicksilver and Country Joe and the Fish were great bands, but they were indeed psychedelic,though the Fish gravitated more towards jug band music, and Quicksilver the blues.

However, though the Airplane could indeed be classified as a psychedelic band, they embraced what I think is the essence of real rock ‘n’ roll, and that is attitude.

It was the Airplane, who with White Rabbit encouraged us to “feed our head” as part of what I consider a favorite all time album of mine, Surrealistic Pillow.

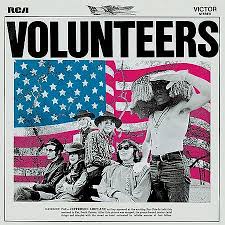

That disc followed Takes Off, which featured the band’s first drummer, Skip Spence, who then fled to Moby Grape (another great, albeit tragic band), and female lead singer, Signe Anderson. One the heels of Pillow came After Bathing at Baxter’s and then the wonderful Crown of Creation, but it was album #5, Volunteers, that really sealed the deal of the Airplane owning the the title of best band of their generation. That is because very few albums until then were as in your face as was Volunteers.

Aside from the faux salutes and homage/parodies to Old Glory all over the liner notes and inserts, the opening track , We Can Be Together, announced that as “outlaws in the eyes of America,” we would “cheat lie forge fuck hide and deal.” Equally menacing, the song then screams “Up against the wall, Up against the wall, motherfucker.”

The Farm implies the pastoral life romanticized by Flower Power is the way to go, and the beautiful pairing of the post-apocalyptic Wooden Ships (co-penned by David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Paul Kanter) and Kantner’s adaptation of the lovely Good Shepherd, with the haunting guitar of Jorma Kaukonen might be demure compared to the fuck you of Together, but they never-the-less indicate there is a different path out there and we are on it, like it or not.

There is also the symmetry of the title track and closing cut, that screams “Look what’s happening out in the streets, got a revolution, got to revolution,” riffing off the Goodwill-like spiritual renewal organization Volunteers of America, shouting out just that: We are volunteers of America.

And, though spiritual renewal may indeed be what author Kantner was pointing to, it was certainly not a Salvation Army style one.

There are other parts of the album, like the half sides of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich–something so American–on either sides of the inside of the album, so that when closed, there was indeed a complete sandwich, albeit in just two dimensions.

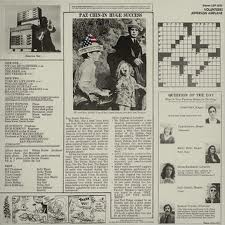

Finally, there is the newsletter from the Paz Chin In, a Woodstock take off, that in the text gives us the lyrics (it was still the 60’s, so fuck is replaced by the word “fred”) plus cartoons, baseball stats (with a great subtle homage to local hero and SF Giant, Willie Mays), a goofy crossword puzzle with no questions but cryptic squares, and a funny reminder that says, “Neil Armstrong, first man on the moon.” However, the first is crossed out, and replaced with the word “last,’ and at the time it was true, that Armstrong was first and last.

We are also reminded in the notes to “feed and water our flag,” among other suggestions

In my mind, there is no other statement by any band in the counter culture that ever embraced art and music and sentiments in such a fashion. Within Volunteers, Jefferson Airplane pushed the agenda of “we are forces of chaos and anarchy,” sneering at the status quo while also supplying a deadly combination of cuts in here-to-fore uncharted territory. In fact, nothing else was even close.

Of course the band did rankle in other ways. Like Grace Slick trying to get into the White House to then first daughter Tricia Nixon’s tea for Finch College graduates. Slick, as alumnae, was invited, and did try to attend. However, the singer was not allowed entrance. According to Slick, she and her date, Yippie Abbie Hoffman, were pulled out of the entrance line and denied because they were on the FBI watch list at the time.

Per Slick, all the Airplane were on the list for “suspect lyrics.” Also per Slick, she did try to sneak LSD in to slip Nixon the father–hardly beloved by the left at the time–a mickey (presumably in his cottage cheese and ketchup).

Jefferson Airplane did release a few more discs after Volunteers–Bark and Long John Silver–but they never had the bite of Volunteers. The band did release a terrific live disc, Bless it’s Pointed Little Head that captures everything that is Airplane, and features a brilliant cover of Fred Neil’s The Other Side of this Life, which opens with a Jack Cassady bass-line, that is then joined by some deadly interplay by Kaukonen, then Dryden, and the best of the band systematically joining in.

If the Airplane peaked with Volunteers, they then slowly landed, re-emerging as Jefferson Starship, which was a Kantner/Slick/Balin endeavor to start, but quickly the principles abandoned ship, and the group morphed into the Starship, which really had nothing to do with anything Jefferson at all.

However, Kaukonen, Cassady, and the late Covington did form their own spin-off, Hot Tuna who did stay true to the folk-blues roots that signaled a lot of the original band’s sound in the first place.

Certainly, the Airplane, and especially the then exotic and brainy Slick, with the powerful voice, generated a lot of buzz when they entered the eye of the public at large, but to me at the time it all seemed in the context of the media trying to be or act hip. And, though Slick was indeed a great character, the real story was what a killer band the Airplane really was.

More to the point, they were a great band that embraced the “fuck all of you in the mainstream” principles that are the essence of rock ‘n’ roll.

Bang Bang. Maxwell’s Is Nearly Dead.

There are bars with music and there are legendary bars with music. Maxwell’s, in Hoboken NJ, will be one of the legendary ones for just another two months. I lived in Hoboken in 1981, when Maxwell’s, just three years old, wasn’t yet venerated. At that time it was too new and too exciting, regularly booking the same bands that were playing CBGB, across the river, and serving as something of a home club for Yo La Tengo and the Feelies, among others. During my Hoboken days I remember going to see bands at Maxwell’s, drinking beer at Maxwell’s, having brunch at Maxwell’s, but I don’t remember at this point what bands I saw at that point. At that point the point wasn’t the names, but the music, which was still lively and energized by punk, hugely broadly do it yourself, full of folks making their own legends (and sometimes succeeding) making rock or what became known as Alt-Country, in a movement that changed the tastes of the nation.

There are bars with music and there are legendary bars with music. Maxwell’s, in Hoboken NJ, will be one of the legendary ones for just another two months. I lived in Hoboken in 1981, when Maxwell’s, just three years old, wasn’t yet venerated. At that time it was too new and too exciting, regularly booking the same bands that were playing CBGB, across the river, and serving as something of a home club for Yo La Tengo and the Feelies, among others. During my Hoboken days I remember going to see bands at Maxwell’s, drinking beer at Maxwell’s, having brunch at Maxwell’s, but I don’t remember at this point what bands I saw at that point. At that point the point wasn’t the names, but the music, which was still lively and energized by punk, hugely broadly do it yourself, full of folks making their own legends (and sometimes succeeding) making rock or what became known as Alt-Country, in a movement that changed the tastes of the nation.

The first show that I remember going to see at Maxwell’s by design involved commuting across the Hudson River via the PATH train to see the legendary British punk band the Mekons, whose amazing country record (and that does not do it justice) was called Fear and Whiskey in the UK and had just been released in the US (with some extra tracks) as Original Sin. The room with the music at Maxwells was small then (and is still the same small), an irregular box with a myriad of obtuse and acute angles on the perimeter, plus columns in the middle, kind of the shape of a game controller, only you’re on the inside. There were some chairs and boxes for sitting around the edges, a bar in the back, and the band was crammed into a nook at the other end of this rhomboid box, crushed amidst whatever speakers and amplifiers were stacked up there to help them make noise. The Mekons that night had at least seven people jammed on the stage, and it seemed like 20, playing the usual guitar, bass and drums, with Sally Timms on vocals, and also a fiddle player and an accordion player and a few others who banged on things this and that and who sang along, too, at the sing-songy parts.

The room was packed with expectation on June 20, 1986. The Mekons had always been a political band, but arch, funny, engaged, enraged, also aware they they were playing music ferchrissakes. Their first single, released at the height of punk mania, was called “Never Been in a Riot.” Unlike the Clash.

The room was packed with expectation on June 20, 1986. The Mekons had always been a political band, but arch, funny, engaged, enraged, also aware they they were playing music ferchrissakes. Their first single, released at the height of punk mania, was called “Never Been in a Riot.” Unlike the Clash.

Their music in 1977 was brittle, angular, clangy, totally amateur. They couldn’t play. A legend arose that if you learned to play your instrument the Mekons kicked you out. The Mekons were masters of the ethos of the naif, the beginner, but over the years their chops improved and their ambitions grew. Jon Langford developed as a guitarist and songwriter. He fell in love with Hank Williams and he steered the band toward the fabulous hybrid they developed in Fear and Whiskey. It’s country, but not afraid of reggae and afropop, in places, homespun but raging with anger about the injustices of the Reagan/Thatcher years and the darkness at the heart of the soul. And that isn’t the half of it. Love songs, sex songs, passion, history, politics, metaphor, but most of all joyous strange music that often sounded trad., music from the ages, but was played by a big rock ensemble with passion and craft. It was was wholly original, like nothing exactly you’ve ever heard before, but full of the spirit that courses through your soul, maybe like marrow. At least on your good days.

This was quite suddenly a band at the top of their game, at the top of anyone’s game, Fear and Whiskey representing the first of a string of maybe five albums (Fear and Whiskey, The Edge of the World, The Mekons Honky Tonkin’, So Good It Hurts, Rock and Roll) that are as first rate as any such sequence in rock history. This was a band for whom the motives seemed to be purely moral, large of heart, full of sensual pleasures that come from making great rocking music with your friends. That sweaty woozy hot night at Maxwell’s I had the unalloyed joy of being in a packed room full of people who were becoming members of the band that was up on stage, the audience pushing them hard, the band embracing their fans and embracing the push, and making music back at us! Encouraging us! By the end we felt like we’d been invited onto the tour bus for the rest of our lives, and while we get off here and there, the many times I’ve seen the Mekons live since, as soon as the band comes on stage, it’s like you’ve never really been away. We’re all serious friends, here to laugh and to grouse together. Together.

Maxwell’s owner announced this week that the club was closing. In this obit in the New York Times owner, Todd Abrahmson, said that they could probably make the business work for another year or two, but that the changes in Hoboken’s demographics make the club’s demise inevitable. “If you think of Willie Mays playing outfield for the New York Mets — I didn’t want us to wind up like that,” he said.

Abrahamson now books the Bell House in Brooklyn, which happens to be on my street, a few blocks down the hill in Park Slope, and where I saw the Mekons play last year. Somewhere I have a file with a recording of that show, but what I was really excited to find was a recording of that show at Maxwell’s back in 1986 at archive.org. Not like being there, but a swell souvenir and not a waste of your time.

It’s No Use Calling, the Sky is Falling, and It’s Getting Pretty Near the End

I love the movie Almost Famous.

I love the movie Almost Famous.

Aside from the work being a terrific piece of cinema, I was a subscriber to RollingStone when the original article–written by Cameron Crowe and based upon the Allman Brothers Band tour–on which now director Crowe’s film is based, was published. I remember the words and for sure the photographs.

I am also a big fan of Phillip Seymour Hoffman, the chameleon actor who portrayed Truman Capote, Scottie (the neurotic “go-for” in Boogie Nights), Brandt, the other Lebowski’s ‘go-for,’ Athletics manager Art Howe (in Moneyball), and my favorite, tragically doomed rock critic Lester Bangs in Crowe’s tome.

In a typically Bangsian rant, the actor dismisses cool bands–including the Doors and Morrison Hotel–, extolling the 70’s band, The Guess Who thusly: “Give me the Guess Who. They got the courage to be drunken buffoons, which makes them poetic.”

Well, over the last few months we have been having work done to our home, and that meant storing a bunch of crap in what usually masquerades as my music room. Actually, I love the room. All my guitars and array of amps live in there, along with a drum kit and a keyboard. I have a a little PA, and all my music books (some songbooks, but I am talking Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung type books) in there as well.

There is also a stereo–with a turntable no less–and all the 800 or so albums I collected before albums and their moniker became things of the past.

So, with one phase the reconstruction completed, my niece and music bud Lindsay came over not just to help me put stuff in order, but to redo the albums, placing them in band name/release date order a la High Fidelity.

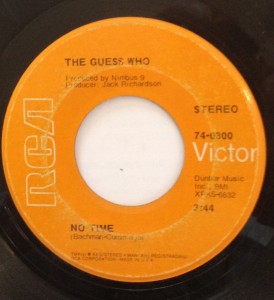

In the course of going through things, I happened onto my old single of The Guess Who’s, No Time which I suppose I have lugged around from house-to-house for the past 40 years or so.

I guess in a Proustian/Swann’s Way fahion, stumbling across the record brought back a flood of Guess Who memories. Like remembering that Burton Cummings had appeared as “an eligible bachelor” on The Dating Game (he wasn’t picked) and the Hoffman cum Bangs line from Crowe’s movie.

In retrospect, Bang’s observation of the band as a bunch of “drunken buffoons” is kind of harsh (but, that is Bangs). Although I don’t know the particulars of their habits regarding the ingestion of alcohol, let alone pyschotropics, but I do know that the Guess Who had a litany of hits.

Between 1968-76, the team of Cummings and guitarist Randy Bachman (the Bachman of Bachman-Turner Overdrive) penned/released no fewer than 32 singles that registered on the Top 100 of one, if not all the charts for Canada, Australia, and the United States.

Of their songs that really clicked in the States, both American Woman and No Sugar Tonight/Mother Nature (the song the title for this piece was stolen from) hit #1.

But, there are a number of great pop tunes within the group’s catalog, including the amazing output list below over a three-year span:

- These Eyes (1969)

- Laughing (1969)

- Undun (1969)

- No Time (1970)

- American Woman (1970)

- No Sugar Tonight (1970)

- Hand Me Down World (1970)

- Share the Land (1970)

- Hang Onto Your Life (1971)

- Albert Flasher (from 1971, and which is part of the Almost Famous soundtrack)

The group still released songs after that fruitful period, but nothing apparently as strong, and they barely registered a flicker on any chart other than their native Canadian one.

They continued to perform as the Guess Who until 1975, split up, and then–shudder–reformed and are still apparently playing to my fellow boomers who refuse to let go of the past.

Irrespective, that list of ten tunes above deserves more merit than even Mr. Bangs could offer.

Both These Eyes and especially Undun were just great tracks at the time, with the flute in Undun pre-dating Jethro Tull and Ian Anderson by a couple of years.

No Time is simply a great song, with a cool drum kick that starts the groove off. And there are similarly the vague and cool words:

“no time for my watch and chain,

no time for a summer rain,

seasons change and so do I,

you need not wonder why,

for no time left for you…”

OK, so maybe a little hippy dippy trippy, but it was 60’s, and, well, American Woman was probably no less naive in principle. It also rocked enough for Lenny Kravitz to cover in a great way, and it is another song I always wanted to cover in one of my bands.

The apex, though, was No Sugar Tonight/Mother Nature, probably the band’s maximum opus that sort of merged together two tunes eventually pulling the melody from No Sugar for the coda and finish.

Certainly, Cummings, Bachman, et al, were not The Stooges, or even the Seeds or the 13th Floor Elevators in the world of in your face Rock’n’Roll.

But, for a brief time, right when FM radio was taking off, and baby boomers were determining that “Up With People,” and “The King Family” were not really what represented music and the future (check out the first 20 years of Super Bowl halftime acts, and you will see), and no one really knew what direction we were supposed to go, let alone would go, The Guess Who popped out some pretty good and tuneful tunes.

To me, they were even more than drunken buffoons. They still are.

Phillip Lynott, Irish Prosodist and Rocker

Moyer lists Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak on his greatest albums list, and James Parker at Slate points out just how nimble a lyricist Lynott was. Nimble enough to have a Dublin statue of his own on Harry Street.

Moyer lists Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak on his greatest albums list, and James Parker at Slate points out just how nimble a lyricist Lynott was. Nimble enough to have a Dublin statue of his own on Harry Street.

The Doors are not remnants!

But this interview on Fresh Air with Ray Manzerak, who died today, is pretty amazing.

But this interview on Fresh Air with Ray Manzerak, who died today, is pretty amazing.

Who makes a hit? Is it John Coltrane? Is it the keyboard player in a band with a charismatic lead singer? Or the chops the band brings, which are very sweet. Listen here.